Warning: spoilers for the book and first three episodes beyond this point!

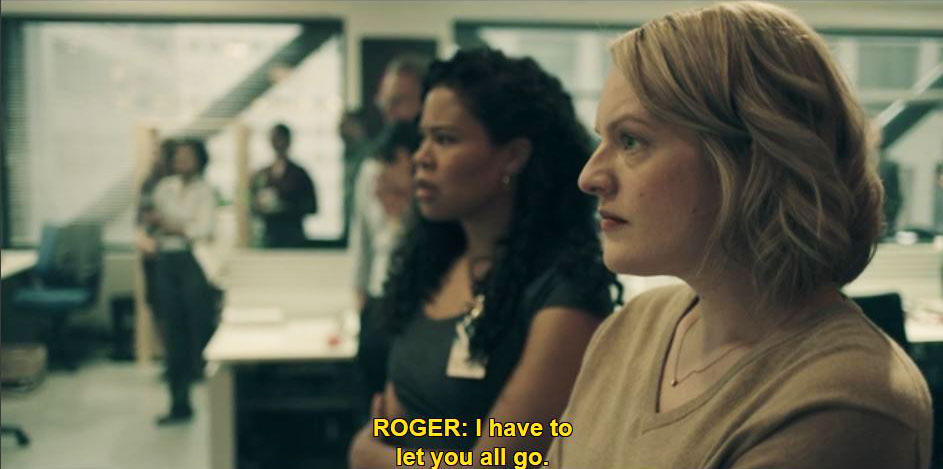

After the first three episodes of The Handmaid’s Tale aired on Hulu, folks were rightfully horrified by the scene where June (later known as Offred) and her fellow women coworkers were fired; the women in that fictional world also lost access to their bank accounts and credit cards, ushering in the Republic of Gilead, the authoritative regime that took over the country. While this scene was chilling, it didn’t impact or disturb me as much as intended. Why? Because this dystopian fiction is a reality for many disabled people, especially those who are multiply marginalized – like queer and trans disabled women of color. As a disabled latina, I’ve already lived through, and continue to live through, that scene in the show. Let me break down what I mean.

Disabled individuals receiving Medicaid and SSI for life-saving services are only allowed to have $2,000 to $4,000 at any given time, depending on where you live; and SSI/Medicaid only includes those who successfully navigated the system with access to a doctor and formal documentation. If we can work, our Medicaid is at risk – the Medicaid that gives us the help we need to get out of bed in the morning. Some states have work-incentive programs like NJ’s WorkAbility, but our salaries are capped; if we make over the limit, we can lose our Medicaid. If you get married, your spouse’s salary counts toward your income – so marriage equality is beyond our reach. Without family or loved ones able to step in as caretakers, many disabled people are institutionalized against their will, with little hope of getting out alive. These truths are not historical anecdotes or stories conjured up by a talented, fantastical writer – these injustices are happening now, in the United States and other countries.

But there are changes happening now, too – changes that aim to right the wrongs. With the introduction of ABLE accounts, disabled people can open a tax-free savings account that can hold up to $500,000; this is touted by politicians as a significant step toward equality, but as with most things related to disability and government, there are caveats. To open an ABLE account, your disability must have developed before the age of 26; this rule excludes anyone disabled via injury or diagnosed later in life. You can only use money in the account for “Qualified Disability Expenses,” like doctor’s visits, housing, and transportation; if you withdraw funds for something unqualified, the IRS can come after you with a hefty tax penalty. Annual contributions to the account are capped at $14,000, and in the instance of your death, Medicaid can file a claim to steal money from your account to repay their expenses.

For disabled people, our money is not our money. The government punishes us for working, with the looming threat of losing our health care. And for those of us who can’t work, we live on an average of $700 per month from SSI; and with a system that is frustrating to navigate and sorely outdated, you are still penalized for sticking to the rules. I had to call Social Security over four times to declare my current job, giving my information over and over because they didn’t see me in their system. Then they sent me a bill to repay my SSI because I “never claimed” my job. They thought I was cheating them, yet it was the other way around; this is nothing new in the life of a crip.

Our government tells us we shouldn’t work, and disregards and vilifies those of us who can’t work. This is not hyperbole; it’s just part of our history as a nation, and it continues unrelentingly. The Handmaid’s Tale is a warning for us to keep fighting, to not get comfortable or used to the chiseling away of our rights. There’s a great quote from the book, which they repeat in the show: “Nothing changes instantaneously: in a gradually heating bathtub you’d be boiled to death before you knew it.” Atwood’s work is a cautionary tale about making the un-ordinary feel ordinary, but we are already at the boiling point.

More on Disability in The Handmaid’s Tale

Check out our roundtable discussion and my Geeky Gimp Riots segment from last week’s Geek Girl Riot.

Here is the transcript of my segment:

[show_more more=”Click to Read” less=”Click to Close”]

Hello, everyone, Erin here with another The Geeky Gimp Riots segment; this time, I’m talking about disability in The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood. I read it for the first time a few weeks ago. I knew the general themes going in since the story is so well known, but I was excited to get through it – especially since my fellow Geek Girl Rioters are huge fans. And I ended up loving the book, and thought Atwood created a story that is timeless. The parallels between the world of The Handmaid’s Tale and the political climate today – well, terrifying is putting it mildly. But what I didn’t expect to get out of the book was disability content. And it was there – maybe not front and center, but Atwood gives us these little hints to let us know how that society views disabled people.

Babies born with disabilities are called “unbabies.” Atwood writes: “We didn’t know exactly what would happen to the babies that were declared unbabies. But we knew they were put somewhere, quickly, away.” This line made my stomach churn. Not because it’s unimaginable, but because it’s true to the history of disabled people. It’s true to RIGHT NOW. Globally, disabled people have been and continue to be shut away in institutions, segregated from society – and this includes babies and older children. Instead of receiving in-home care to live in the community, we are forced to depend on loved ones for help. And if you don’t have family, friends, or significant others to help out? We are sent to nursing homes, even though in-home care is cheaper. Now ask yourself this (as Margaret Atwood asks in the book) – who profits from segregation of disabled people? Who profits from dehumanizing marginalized people? The answer is the same for in the book and the real world – those in power – the white, wealthy patriarchy.

But we also see how disabled people are exploited for capital gain. In one chapter, Atwood talks about The Guardians, who are soldiers quote unquote “either stupid or old or disabled or very young” and therefore not real soldiers. The Guardians are used to fuel the system, but their lives are not respected. Similarly, in the real world, we have sheltered workshops where disabled adults are given repetitive tasks for companies and are legally paid sub-minimum wage. Yes, legally. And we’re talking way below minimum wage, some even less than a dollar an hour.

In the new Hulu show, The Handmaid’s Tale only tackles disability in an ableist way, meaning physical disability and mental illness are meant to scare the people watching the show. In one of the first episodes, we are shown someone with one eye, and the way the camera lingers with ominous music, it was apparent we were supposed to find the physical difference creepy. The book, on the other hand, shows how violence in the system leads to disability, and how that disability is then a justification of genocide. It’s meant to shock us by showing what’s wrong with the social and economic system, instead of shocking us by the disability itself. I’m curious to see how disability plays out in later episodes, if it does at all.

So on that cheerful note, I’m interested to hear what you think about disability in this book – send a tweet to us @geekgirlriot. Until next time, keep rioting.

[/show_more]

Let me know what you think in the comments, and share your experiences reading The Handmaid’s Tale, or watching the Hulu show.

Much thanks to Noemi Martinez for her help in editing and pre-reading this post. If you’re looking to support a queer woman of color, single mama, and a badass poet, check out her editorial/historical/writing services page.

Thanks for the article, I haven’t read the book yet or have seen the show, but this is a solid article

Thanks for reading and commenting! Let me know if you ever watch/read it 🙂

I am so excited to come across your blog. I am studying emerging media communications and I am visually disabled myself. I am going to use your article for a presentation on class and disability. Thank you for taking the time to bring awareness to the different-abled community!

That’s awesome, thank you! I hope your presentation goes well.

Margaret Atwood often states that the book is not ‘fantastical’ or ‘science fiction’ as such, because she put no background into the book (and her other books too) that has not already happened somewhere. So she was aware of the reality of certain segments of society not having control over their own money.

Does that make it more scary?

You need to pay better attention. The one eye was a punishment for disobedience, not a disability. The character is not disabled or meant to be considered so.

I was paying attention. Blindness in one or both eyes is a disability regardless of how one becomes blind.

Actually, It’s both. I agree with Hulu’s the Handmaid’s Tale making it creepy because it was a punishment though.

I’m looking into disability in dystopian literature at the moment and these were really interesting insights, especially the current day comparisons, thanks!!

Oh God you brought this home, at this moment I have aged out of my father’s insurance (I have difficulty with employment despite education) and while we are trying to get something, there could be a chance I could get MediCal (I live in Cali) but my Mom claims I can only keep 1,000 dollars in my account and we’d probably have to set up a different account. I feel this is unfair, I am earning money fair and square, working, trying to make my life better, trying to be financially independent but I’d be regarded with suspicion while billionaires and millionaires get tax breaks and and buy whatever number of yachts and mansions and not be looked down on for hoarding wealth.

Yeah, I hear you completely. It really sucks.

As far as the Hulu series dealing with disability, I thought they did well. When they show Janine with one eye, it is horrifying because she had two perfectly good eyes. Then, the Aunts had one of her eyes gauged out as a punishment. Most of the disabled people they show were similarly maimed. That’s creepy as hell. Gilead in the Hulu series calls any child born with a disability a shredder baby. They had a scene in an episode where a bunch of disabled women are separated from women who Gilead seemed to think were useful to their society. It’s really disturbing because they never go into what happens to these less desirable women by Gilead standards. It’s disturbing how they deal with all marginalized groups. What happens to people with psychiatric and similar issues in Gilead is horrific.

The most disturbing part of the Handmaid’s Tale is that it shows things from actually history. It shows things that have actually happened to people. It shows how much intolerance can poison people and society. It shows how easy it would be for fascism to take over a society.

Until we have societies that treat people how they want to be treated and takes care of all of it’s citizens, we will always be moving towards fascism and dystopia. I have several disabilities and I’m not even sure if they are neurological or psychiatric. I’m also autistic. I’ve been treated like less my whole life. Even people trying to help me made it worse. Because I was in special education at school, my teacher’s in elementary school ignored me when I said I was being abused by my parents. I have been discriminated against at work and in the community. I’ve been harassed and abused by police, teachers, medical staff and medical professionals.

Our society needs to change and I’m glad the Handmaid’s Tale has put a spotlight on injustice. I love shows that spotlight injustice. I love shows that show people changing how they view others to stop discriminating against them. Sometimes, people’s eyes just need to be opened.