- 10Shares

Guest post by James Cole

I have an odd reputation among my gaming friends.

Apparently, I’m a good game teacher.

That by itself is not weird. But if you combine that with the fact that I have a visual processing learning disability, me being a decent teacher is not an obvious connection.

In understanding my LD, I’ve had to learn how I learn, and how it’s different from the way others learn. I’m way better at remembering things I’ve heard than things I’ve seen. I have to ask a lot of questions when I’m encountering a concept I don’t understand so that I hear the answer.

One of the ways I looked at my LD was by taking some courses about teaching adults. It’s given me a better understanding about how others learn. It also showed me how I have to adapt to work with how others teach.

Those experiences have all combined to make me look at teaching in a holistic way, and to do my best to be totally inclusive both teaching the rules and about the hobby.

Teaching is a process, and I’d like to share with you what I’ve learned about how to teach a board game.

Establish Your Baseline

Figure out where your students are in their gaming experience. A brand new player might need a lot more explained to them, while a video game player might have some similar concepts that they can understand.

Either way, pick a game that’s at an appropriate level for the group you’ll be teaching.

Tailor Your Game by Theme and Accessibility

A game’s greatest advantage is its theme. Players are more likely to be engaged with a game and more open to the rules if the theme speaks to them.

Good theme integration also makes a game easier to explain. For example, games that use hidden movement as a mechanic, where one player hides their position while the other players try to find them, are usually themed for espionage, crime, or horror. This gives the rules of the game context, and a reason why rules are interlocked the way they are. It also aids in suspension of disbelief while playing.

However, there are some themes that will be alienating. Sexual objectification, cultural appropriation, and colonial bias are in too many games to mention this post. They can make a new player uncomfortable, and potentially chase them away from the hobby for good.

Accessibility is also something to consider when picking the game to teach. This is difficult because all games feature some form of challenge, which will be inaccessible to someone.

Keep these factors in mind when selecting the game, and you’ll find your group open to what you’re exposing them to.

Learn the Game Yourself

This might seem obvious, but you can’t teach something you don’t know. Being “taught” by teachers who have no idea what they were talking about is unpleasant.

Learn the game in advance.

You want to know the game well enough to teach others to play it, but you don’t need to know so much that you can play competitively at a world championship level. Understanding the mechanisms, structure, and flow of the game is enough.

“Know Thyself”

Understanding how YOU learn things is handy at this point.

Having a handle on your preferred learning style will guide you to the resources that best compliment your strengths. An aural or visual learner will likely benefit from a YouTube video explaining the rules, while a kinesthetic learner would probably get an advantage from setting up the game by themselves and playing a few rounds solo.

Remember, this isn’t school, and you are not being tested on this. Use any resource that you can find that you think will help you. YouTube has lots of rules explanations, and Board Game Geek has many teaching and player aids.

On top of that, you’ll be sitting at the table during the game to clarify rules questions.

Set the Stage

Set the game up in advance. Not only will it save time for your players, but you’re setting the stage with your essential prop.

When your players are seated, you begin you need to answer three questions immediately.

1 ) What are we doing?

2) How do you win?

3) Why are we doing it?

The first question let’s you explain the theme and the story, and let’s you hook the players with visions of fantasy valor, post-apocalyptic wit, or interstellar guile. Summarize the games’ theme in a quick, engaging way. Using Carcassonne as an example:

“It’s a competitive jigsaw puzzle.”

The second question introduces the rules and mechanics. Touch on rules briefly as this is a just the introduction. Describe the very basics, but make it clear how someone would win.

“We’ll be laying tiles and placing meeples to claim areas which are worth points. The most points at the end of the game wins.”

Finally, let your players know why you think this is fun. Will it be a passive-aggressive struggle? A tense backstabbing affair? Glorious schadenfreude? Let the players know what behavior the rules will be bringing out, and to paraphrase Gil Hova, what behavior will be incentivized.

“We’ll spend the next 40 minutes cutting each other off, destroying each other’s opportunities to grow, and brutally competing for farms.”

Nuts and Bolts of The Rules

After your players have a general understanding of what’s going to happen, you can start to get more specific on how things function.

From there, introduce more concepts by starting simple and increasing in complexity. I like to start using the smallest possible thing in the game, and expand out.

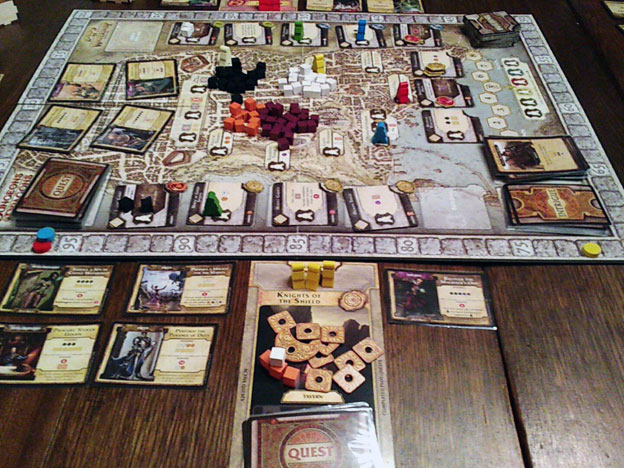

Using Lords of Waterdeep as an example, I’d start this teach by introducing the resources of the game (adventurers and money), where you get resources (action spaces on the board), how you get resources (turn structure), how you get points (completing quests), and how the game ends (round structure and hidden scoring objectives).

While explaining, get the players to play out the actions you are describing. Get your players involved on multiple levels by having them listen, see, and touch. The game is an excellent prop – use it.

As mentioned, the theme is a strong tool. Take advantage of it. Good themes help reinforce the mechanics of a game, and make it easier to understand. Lean into the theme, and have fun with it.

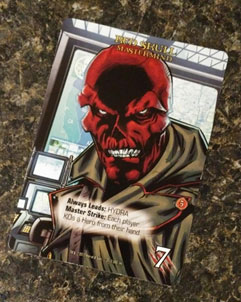

Identify any rules that you can introduce during play that won’t interfere with the game until they come up. Legendary: Marvel is a good example. The rules to this co-op deck-building game are surprisingly straight forward. The game takes a turn, the bad guys advance, the next player in turn order plays their hand, and the cycle repeats.

Legendary becomes more difficult one you start introducing individual cards and their keywords. A lot of these can wait until they come up during play, and then be introduced organically.

Be Flexible

Teaching requires patience, preparation and adaptability. This goes for students of all types, disability or not. Be prepared to explain something in multiple ways if one of your students doesn’t understand something.

Get Going

Pick a game that connects with your players, learn it in advance, and work through the rules in an organized way.

Then, most importantly, have fun.

Now, let’s play!

Guest blogger: James Cole is a freelance writer living in Barrie, Ontario, Canada. He was diagnosed with a Learning Disability in Grade 4, in the wild and lawless 1980’s. James belongs to two board gaming groups, just started running a D&D campaign, and is wildly uncomfortable writing about himself in the third person. Yelling at James can be accomplished on Twitter, and you can judge his board game collection on Board Game Geek under the handle talentdepot.

Become a Patron!

1 thought on “Learning Disabled and Teaching Tabletop Games”