Guest blogger: Aimee Louw is a freelance journalist, writer, consultant, filmmaker, and radio host living in Canada. Her blog centers on accessibility, crip life, sex, and media.

Based on a true story, Breathe covers the adult life of Robin Cavendish, a man who contracted polio in post-World War II England, when requiring a ventilator to breathe meant across the board institutional living and immobility. The story follows Cavendish’s journey from active and horny young man, to newly-disabled, depressed institutionalized patient, to disability advocate/ innovator. There is a large focus on the triumph of love prevailing over despair with his wife, Diana. As the trailers began, I popped some painkillers, and I settled in with my non-institutionalized boyfriend, J.

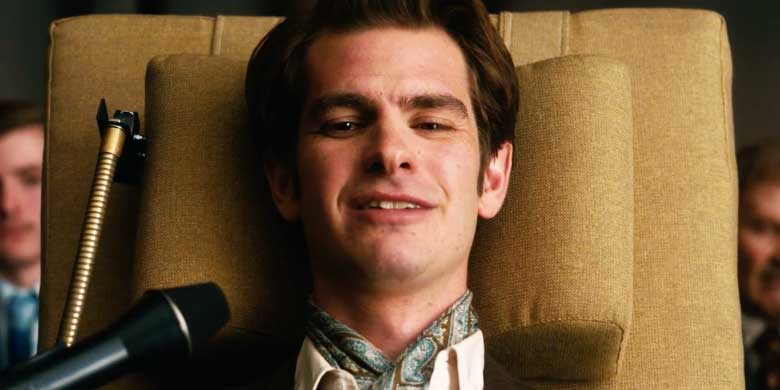

The film opens in an idyllic English countryside, with voracious young men playing cricket. The main character, played by Andrew Garfield, ogles with other young men at a pretty lady, Diana, played by Claire Foy. The swells of orchestral music that accompany the displays of Robin’s physical prowess forebode trouble looming for this strapping young man.

Cavendish contracts polio, and as he lies in a dark wooden room, lined up symmetrically with other patients, we are struck by the sound of ventilators heaving like non-melodic accordions. In this haunting setting, it becomes clear that our recently-paralyzed main character does not want to go on. The prognosis is grim. As the doctor tells his wife, “it’s no kind of life, Diana”, J looks over at me with a sarcastic grin. After some heartfelt deliberation, Robin and Diana agree: either he escapes the hospital and lives, or he dies there.

What follows is a whimsical and adventurous escape, involving complicit nurses, friends, and family. So playfully portrayed was the escape, that in a way, it downplays how completely unprecedented and radical this act really was.

As he settles into his new freedom, he gets the idea for the first wheelchair with a mobile ventilator on it. His inventor friend, Teddy Hall, designs the ‘Cavendish Chair’: a stately, cushion-lined chair, with thin wheels and bicycle chains. Robin wears his chair very well, with on-point bow-ties and suits. The film shows the relatable fear of travelling with adaptive technology when a ventilator malfunction occurs on a windy road in Spain.

An important thread in the movie is Robin’s recurring thoughts of his friend and comrade from the hospital. After the ‘Cavendish Chair’ is developed, Robin brings it back to the hospital to empower his friend, strutting in on the chair, and snubbing the doctor who told him he couldn’t leave the hospital. This nods to crip solidarity, and a personal fantasy of mine: shoving crip victories in naysaying doctors’ faces.

Cripping Up in Breathe

While I found Breathe genuinely moving, I have to address how bored I am of watching non-disabled actors crip-up for the big screen. In an interview, when pressed about playing a disabled person, Andrew Garfield explained that his character had to be able to play Robin Cavendish prior to, and after paralysis, therefore requiring a non-disabled actor. We have CGI graphics portraying characters appearing in space and exploding in fiery doomscapes, so needing to CGI a disabled actor to make him appear non-disabled for one scene would work just fine. In playwright, Christopher Shinn’s 2014 Atlantic article, he argued for more disability representation on the big screen, that non-disabled actors being able to leave disability in the studio reassures non-disabled audiences from their cultural fear of disability. As a believer in crip community as a subculture, I would even say that non-disabled actors playing disabled characters is a form of cultural appropriation.

As the story nears its end, Robin throws a goodbye party for himself, as he prepares to ‘let himself die’. J grumbled in his seat, and I wondered how much time in the movie was spent on contemplating death. I am sensitive to narratives of disability that center around suicide and end of life discussions because I am concerned with giving non-disableds more impetus for the pervasive belief that disabled lives are not worth living. But, with Breathe, I feel more generous and can’t easily write the movie off as ableist propaganda (as I often do), because the main character’s real-life son is the producer, and maybe this was a big part of the memory of his father. Then again, favoring the perspectives of non-disabled family members, while perhaps more palatable for a general audience, de-centers the perspectives of real live crips, which is undoubtedly paternalistic.

Despite the cripping-up, I would recommend the entertaining and romantic, Breathe. At a time when austerity tightens homecare budgets and institutionalized living is a reality for many disabled people – including present-day ventilator users, this story is worth watching. We need reminders of those ground-breakers who had the means and support to bust out of institutions, refusing to live the way the state saw fit.

Robin Cavendish pushed a lot of boundaries and contributed to a lot development and innovation in disability rights post-World War II Europe. I hope that one of the next frontiers of our time – that of disability representation and agency, also gets pushed both because of this film and, alongside it, with more disabled actors being hired to fill the roles of disabled characters.

Suggested next read: Doctor Poison and Disability in Wonder Woman